Symposium “Survival of Older Persons under the COVID-19 pandemic in Asia and Africa: Exploring Community and Health System”

Symposium “Survival of Older Persons under the COVID-19 pandemic in Asia and Africa: Exploring Community and Health System” will be held online at the 36the Annual Conference of the Japan Association for International Health on November 28, 2021.

The symposium was conducted in Japanese.

http://square.umin.ac.jp/jaih36/index.html

How are Older People in Asia and Africa Surviving the COVID-19 Pandemic- In Search of a Resilient Community and Healthcare System –

Introduction

Ken Masuda (Nagasaki University) Slide[PDF]

In Japan, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is often associated with adverse reactions in older people, as evidenced by cluster infections at facilities for the elderly and prioritized vaccinations, which have made headlines since the outset of the pandemic early last year. However, little is known about the current state of international health issues, which the Japan Association for International Health (JAIH) is dedicated to, especially in terms of how older people in developing countries are fairing amid the COVID-19 pandemic. This symposium is an attempt to address such issues from the perspectives of communities and healthcare systems.

Issues with older people have never been a significant topic for the JAIH until recently. Now though, we are seeing an increasing number of reports on population ageing. Last year, Dr. Motoyuki Yuasa of Juntendo University organized a symposium where I had the privilege of taking the rostrum. In a similar vein, at a symposium organized by Dr. Yuasa for the Joint Congress on Global Health in 2017, Dr. Reiko Hayashi, who co-chaired this symposium, took the podium. Further back, since 2012, an open gathering titled “Borderless Challenges of Global Ageing” has been held for eight consecutive years. Organized by Dr. Hideki Yamamoto of Teikyo University and Dr. Nanako Tamiya of Tsukuba University, this annual gathering has provided opportunities for the members of the research projects funded by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) or otherwise to collaborate, and many of the participants in this symposium have taken an active role in it.

At the Seventh Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD7), which was held in Yokohama, Japan, in 2019, our project was asked to organize official concurrent events, which is another sign of growing interest in issues concerning the ageing populations in Asia and Africa.

Population ageing is one of the preconditions that cannot be ignored when designing future human societies. Asia is the most populated region in the world, and with increasing longevity and declining birthrates, the number of older people is expected to increase dramatically over the next fifty years or throughout this century. In Sub-Saharan Africa, on the other hand, there is still no sign of their populations ageing, with those aged 60 and above and 65 and above accounting for an average of five percent and roughly three percent, respectively. Rather, in the case of Sub-Saharan Africa, the interests of demography researchers are currently in the rapid population increase and demographic dividend. Nevertheless, the absolute number of the elderly is increasing at an accelerated pace there, making it imperative to address the difficulties faced by this demographic, including the rapid epidemiological transition from communicable diseases to non-communicable diseases, poverty, or other situations, via fact-finding surveys.

Much remains unknown about the impacts that COVID-19 has had on the lifestyles of older people. As you can see on this slide, infection status varies from one country to another. Some countries have experienced multiple waves since 2020, while Vietnam suddenly saw an explosive spread of the Delta variant at the beginning of 2021, and Myanmar went through the spread of COVID-19 and a coup d’état simultaneously.

If we use daily reports published by Kenya’s Ministry of Health to analyze the by-age numbers of people there dying from COVID-19 in August 2021, when they were in the middle of their fourth wave, we realize that the number of deaths is the greatest for those aged 60 or over.

This symposium is intended to shed light on issues in the lives and health of older people, who are easily marginalized in society, by presenting reports from diverse perspectives of four countries, including three Asian countries and one African country, out of the wish to provide a chance to consider how we should revamp communities and healthcare systems.

Health Situation of Older Adults in Myanmar under the Disasters of Infectious Diseases and Humanitarian Crisis

Yugo Shobugawa (Niigata University)

I will talk about the health situation of older adults in Myanmar under the humanitarian disaster and the military coup. I have no conflict of interest.

I will specifically talk about findings of a cohort study on older adults in Myanmar that we set up in 2018. For the purpose of sampling, we used probability proportional to size (PPS) based on population demographic data. Myanmar is divided into seven regions and seven states, and we chose Yangon Region and Bago Region to represent an urban district and a rural district, respectively. We selected six townships from each region and then ten wards or villages from each chosen township. With the cooperation of ten older adults from each ward and village, a total of 1,200 adults participated in this project. We visited them at their dwellings to do an interview using a questionnaire developed for the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES) project, modified with the social and cultural context of Myanmar in mind. The questionnaire covers a broad range of questions not only on their physical and psychiatric status and activity but also social aspects of their living such as social network, socioeconomic status, and social capital.

The baseline survey for 1,200 persons was conducted between September and November 2018, followed by the first round of telephone surveys two years later in 2020. Between the two surveys, 166 persons dropped out and 51 persons passed away, with 983 persons surviving. We were originally planning to do another round of in-person interviews three years after the baseline survey in 2021, but the country was hit by COVID-19, and then a military coup broke out in February 2021. So, we gave up visiting them for an interview and conducted another telephone survey instead. Of the 983 persons whose survival was confirmed in the first telephone survey, 151 persons dropped out and 42 persons passed away, with 841 persons surviving. My report today is mainly focused on the findings from the second telephone survey.

The second telephone survey was conducted in April 2021. The military coup occurred in February of the same year. According to this graph, in that span of time, almost zero COVID-19 cases were reported, but it is not clear if the infectious diseases surveillance system was functioning properly after the coup, and we cannot really see the epidemic situation there. That said, a comparison with the situations in other Southeast Asian countries during the same period indicates that things were relatively under control in the region around when we did the telephone survey in April.

A total of 93 persons died during the follow-up period of an average of 793 days. Among other findings are that males died earlier, probably because their average life expectancy is shorter, and that those living in the rural district of Bago died earlier. If we look at a difference in basic attributes between the survivors and the deceased at the time of the baseline survey, those who are “male,” “high age,” and “in the middle status of wealth” had significantly higher mortality. A Cox proportional hazard model indicates that those who participate in a religious group or meet friends at least once a week lived significantly longer. On the contrary, those who have no one to vent or voice their concerns to or who have no one to take care of lived significantly shorter. Disability was another significant mortality factor.

This slide shows the situations of older adults in Myanmar in April 2021, when the coup occurred amid the pandemic. The samples include only older adults in both rural and urban districts whom we were able to contact for the second telephone survey. In the rural district, the scores for “self-rated health,” “frailty indexes,” “geriatric depression scale,” “loneliness,” and “sleep quality” were low, while there was little difference in the economic situations between urban and rural districts, except food insecurity, which was a greater source of concern in the rural district presumably because of a limited supply. The survey also found that access to healthcare was worse in the urban district of Yangon than in the rural district because more than half of the respondents said they were not able to go out or had fewer chances for social involvement.

Nursing Education Perspective in Aging Society, the Case of Vietnam

Satoko Horii (Chiba University)

Today, I will look into how Vietnam is preparing itself for the graying of its population, with a focus on healthcare professionals, who constitute the healthcare system that supports their communities and older people.

Let us start with the current status of population aging in Vietnam. They define persons aged 60 or over as older people. Now, “older people” account for 12.3% of the total population, which statistically qualifies as “aging.” When it comes to the aging of the Vietnamese population, we often discuss its speed, as well as its current status, because they are outperforming Japan, which has been regarded as the world’s fastest aging country, in terms of the time needed to move from “aging” to “aged” and from “an aging society” to “a super-aging society”.

Shown here is a comparison between the urban and rural area. In Vietnam, the percentage of older people is higher in rural area than in urban area, particularly among women.

At present, Non Communicable Diseases(NCDs)are main cause of death in Vietnam. Although their healthcare system and lifestyles are improving, aging itself is a risk factor for NCD and hence catalyzes changes in their health issues.

From the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Vietnamese government imposed stringent national social distancing orders, which the population appreciated and followed. As such, Vietnam was cited as having one of the best-organized pandemic control programs in the world—at least initially. Now, COVID-19 is spreading rapidly, with the number of cumulative positive cases is quickly catching up to Japan’s, with the number of new positive cases over the last week accounting for nearly 10% of the cumulative total. The number of deaths, too, has surpassed that of Japan. The vaccination rate remains at around 40%, which seems to have stagnated partly due to the difficulty in procuring vaccines. If we look at the situation for older people, those aged 60 or over account for about 10% of the total number of those infected with COVID-19. Interestingly, more women aged 60 or over have been infected than their male counterparts, when there seems to be no such difference for other age groups.

In response, the Vietnamese government has taken several measures, such as offering financial support for the socially vulnerable, including older people, permitting prior medication orders for them up to two to three months ahead to avoid their frequent visits to health center, accelerating the introduction of telemedicine services, and enhancing functions of community centers.

I will now talk about the nursing profession there . First, they have yet to satisfy the international threshold of 4.45 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 1,000 people. They are also behind other ASEAN countries in terms of a minimum density representing the need for nurses. With regard to job opportunities for nurses and midwives, many of them work at national, provincial, and other large-scale hospitals. This is not because these hospitals have a large number of beds, but they are concentrated in provincial and other hospitals percentage-wise. What I would like to point out last is a gap in the competency of nurses among hospitals. A survey into the competency of new graduate nurses revealed that those working in urban area are significantly more competent than their counterparts in rural area. There are two reasons for this: First, competent nurses tend to seek positions at hospitals in urban area. Second, hospitals in urban area tend to hire competent nurses.

The competency gap among nurses is attributable to pre-servise trainingprogram there. In Vietnam, pre-service nursing training programs are offered at vocational schools, colleges, and universities, but there exist no core curricula or standard curricula common to different courses offered by different institutions, nor are there national examinations to become a nurse. Having completed a pre-sevice nursing training program, trainees obtain a license after clinical training among different employers, which could be one of the reasons for the variation in competencies of nurses. To address this situation, the Vietnamese Ministry of Health implemented a project to standardize clinical training in collaboration with the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), and is working to introduce a national examination for nurses and standardize competency requirements for its introduction. At the same time, they are engaging in a variety of initiatives designed to improve the training of nurses by, for example, abolishing vocational schools in an attempt to raise the levels of basic nursing education.

Now, let me take this opportunity to walk you through pre-service training program there. As I mentioned earlier, because they don’t have standard curricula for pre-servise training in nursing, I will focus on the curriculum of one university in Vietnam that cooperated with this survey. This particular university has a relatively complete and qualified faculty, with multiple professors who earned a doctoral degree in nursing science overseas, and so their curriculum is structured systematically. Please note that not all universities have a curriculum like this becauseother universities and colleges in Vietnam is not so.

Here I compare the curriculum of the Vietnamese university and relevant designated rules in Japan, starting with the required numbers of credits. The number of credits required in the designated rules in Japan is almost equal to the number of credits needed to complete a three-year course in Vietnam, that is, the number of credits required to complete a four-year undergraduate program minus the number of credits for graduate thesis and other classes. If we compare the number of credits for each field, we find that the Vietnamese curriculum had a far greater number of credits for the basic fields and that the same is true for anatomical physiology and other basic professional fields that teach medical knowledge. In comparison, the number of credits for professional nursing fields is relatively smaller in Vietnam than in Japan. This is particularly true for the community-based fields such as community health nursing and home care nursing, as well as gerontological nursing. In addition, the learning objectives and methodologies in their syllabus for gerontological nursing, in particular, were not very clear and some Vietnamese faculty members recoginized that this is the one of the their challenges.

Now, let us look back on the history of nursing education in Japan. The designated rules are constantly revised according to the social needs of the times. Gerontological nursing, for example, was adopted in 1989, when Japan was on the brink of becoming an aging society. The next fiscal year should see the application of the fifth revised curricula. Actually, they began discussing this revision back in 2018, with a focus on what comptencies the nursing professional is required to have, given that the scope of their work has been diversified. Let me give you an example: As today’s nurses are required to play a role in the community-based integrated care system and collaborate and coordinate with other professions and a diverse array of people, the curricula have been revised so they can gain such competencies.

Vietnam is facing a rapidly aging population, combined with a sharp decline in the birthrate. The aging population is expected to increase the needs of care in the community for nursing those with NCDs or in the terminal phase of an illness. What this means is that the percentage of older people among the patient population increases in clinical settings, which should make it necessary for the nursing profession to provide care that takes into account the common traits of older perople. But the hard fact is that they have a scarcity of nursing staff, that nurses with relatively high competencies concentrate in university hospitals in urban districts, and that there exists no standard curriculum for basic nursing education. Generally speaking, they might be able to address these situations by increasing the number of nurses, allocating a certain number of nurses to rural area, combining gerontological nursing and community health nursing in the curriculum of pre-servise education, and further enhancing the in-servise training for existing nurses. Yet, the reality is that such discussions are slow to proceed, which is partially attributable to the fact that different persons involved in nursing education have different ideas. Now, when I say “persons involved in nursing education,” I mean those not only in but also outside Vietnam including the stakeholder in Japan. Given this involvement of diverse parties in nursing education in Vietnam, I believe parties involved must discuss how they can contribute to produce nursing staff who can meet the health issues in Vietnam.

Aging and Women in Rural Area in Kenya: Utilization of HDSS and Anthropological Research

Kaori Miyachi (Saga University)

My presentation today will cover three points. I will talk about the global phenomenon of aging first, and then the need for a gender perspective of focusing on older women. I will finish off with my survey findings on older women in a rural area in Kenya.

Let me start with the first topic: the global phenomenon of aging. As with other parts of the world, aging is creeping into Sub-Saharan Africa. In Kenya, the percentage of those aged 60 years or over was still low at 4.3% in 2017, but it is expected to reach 10.6% by 2050. Population aging in developing countries is linked to various issues, but not much research has been conducted on aging in Sub-Saharan Africa.

These are population pyramids in Kenya. It is expected that the pyramid in Kenya will become more bell-shaped, which necessitates measures against aging.

It is important to take note of a gender perspective in this context. In 2012, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) reported that women throughout the world tend to live longer and fall victim to poverty more easily than men. For example, we tend to incur higher transportation costs to see doctors and medical fees as we get older. Because women’s rights to land and property are more often restricted, and most women receive a smaller pension than men, their social and economic status tends to be more unstable. Another consideration we need to take is that it is primarily women who take care of family members, such as older people and children. Also, in developing countries, they don’t necessarily have public help or mutual help for long-term care (LTC), with the result that LTC is provided by family members. Such being the case, the task of caring for older women is often left to younger generations, such as “daughters-in-law” and grandchildren.

To discuss my third point, I will share the findings of the research I did in Kwale County along the coast of Kenya. In this predominantly Muslim area live a group of people known as the Mijikenda, composed of several ethnic groups including Duruma and Digo. I come from a social anthropology background and have done gender-related research in another area in West Kenya called Kisii County. I chose Kwale County for this research because, as a Nagasaki University faculty member, I became involved in an anthropological research project using the Health Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) for the Kenya Research Station of the Nagasaki University Institute of Tropical Medicine (NEKKEN). There, we are working with the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) to conduct research using the HDSS. We also operate the HDSS in Mbita by Lake Victoria. At the Kwale station, we monitor vital events like birth, death, and migration of approximately 60,000 persons in three areas of Kinango, South Golini, and Mwaluphamba. For this KAKEN-funded research by Dr. Masuda, we will start gathering data in earnest from the next fiscal year, covering information deemed necessary for LTC programs of the future, such as lifestyles and pathology of older people, by adding components related to older people to the HDSS.

This particular project on older people is an interdisciplinary one that involves researchers from diverse disciplines. I am supposed to apply my anthropologic knowledge and have been doing interviews for the past several years with thirty persons: ten from each area. Although this does not make for a large sample, I believe that preliminary information will be useful for understanding of the situation on aging in rural area. the HDSS. One thing I have to mention is that, although I speak from a gender perspective, I cannot say that I’m presenting a general picture as I deal with older “women” only , because it is lack of the men’s perspective.

The past HDSS data on this slide shows that the percentage of older people in Kwale increased between 2013 and 2017. When we organized an international workshop on aging in Kenya and Japan there in March 2014, some participants from Kenya, public offiers and medical personnel, unanimously said that Japan has many older people and a robust healthcare system but that Kenya has few older people. They also said that family members in Kenya can take care of their older relatives, unlike in Japan. That made me have an interest in older persons in Kenya, and so I joined Dr. Masuda’s research team in 2016, as I availed myself of the past HDSS data. To gather quantitative data, I asked thirty persons to wear a “life-corder” for seven days, except while sleeping, to count the number of their steps and amount of activity. Furthermore, as the device doesn’t tell us what activity they engaged in, I had a research assistant visit older women to do an interview on the activity recorded within the last 24 hours. From among those samples, I identified older women who had distinct traits about “care” and interviewed them again between 2017 and 2018. Today, I will be presenting the findings of those household surveys conducted from 2016 to 2018.

Imagine a farming village in Kenya—Perhaps you might be thinking that older people are taken good care of, living together with their sons and grandchildren. Well, there are families like that, but what I learned after starting the project was that may not always be the case. In Kenya, the common form of marriage for older people was polygamy, and husbands were older than their wives in most cases. So much so that wives would end up spending their old age as widows. I also realized that there are more single-woman households than I had expected because, even if you have sons or daughters, they may live far away from their mother for work. In some families, sons and daughters visit their aged mother once every several years at her home, and the way they care for older people is very diversified. If an older woman lives alone and her daughters and/or sons live nearby, they visit their mother to take care of her meals and health. If not, older mothers get to see their children once or twice a year or once a month if they are lucky. Some older women are so lonely that they don’t speak with anyone for years if their family members only come to see them once in a while. As they get older, they tend to develop health issues, but I learned that they do not get enough medical support. In the villages where we have a research station, they do not have private clinics but only have public health facilities called health dispensaries. Yet, older people do not get enough services from those public medical institutions. Older people have all sorts of diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes, and have vision loss in one or both eyes (or have cataracts or glaucoma). Those public medical facilities allocate significant human and financial energy to maternal and child health but the hard fact is that older people do not receive adequate care. Because medical care for older people is not taught at educational institutes and LTC is not on the government’s agenda, medical services for older people are often neglected. Of the thirty persons I interviewed, two were bed-ridden, and one was over 100 years old. It is women who provide care to those bed-ridden women, typically daughters-in-law or unmarried nieces. In the case of a bed-ridden woman aged over 100, her son’s wife, namely, her daughter-in-law, was well over 70. You can easily imagine how physically demanding it is to help her bed-ridden mother-in-law to use the bathroom and move back to the bed. In other cases, women in their 60s or 70s were taking care of their older mothers on a daily basis. The survey helped me to realize that Kenya also has issues with older women living alone and already has a problem with older people taking care of people even older than them. In fact, they have launched a pension system that offers benefits to all people aged 70 years or over (Old Persons Cash Transfer, more details will be given in Dr. Yoshino’s presentation right after my report) in Kenya, but some of them have yet to file an application for some reason. As I have described, population aging, along with poverty, has already given rise to issues, albeit a few, with medical services and people’s lives in Kenya.

COVID-19 has prevented me from visiting Kenya, the last visit was November 2019. But let me spend some time to brief you on the current situation there, as the title of this symposium indicates. I recently came across a newspaper article saying that vaccination uptake is slow in Kwale (Kwale clergy lead campaign for Covid-19 jab, The STAR, November 25, 2021; https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/coast/2021-11-25-kwale-clergy-lead-campaign-for-covid-19-jab/) In the first place, the vaccination uptake rate is slow all over Kenya, which in itself is a problem. People there, including older people, are hesitant to get the jab. According to The STAR, the rate is slow in Kwale because of the fears and suspicions among their people that the COVID-19 vaccine will turn people into zombies, make them infertile or even kill them. From a fact-finding survey with local staff members in Kenya, I learned that they were having a terrible drought at the time (November 23, 2021) there. Due to the shortage of rain that had lasted since October, they were having a severe shortage of livestock feed. Villages in Kwale have few COVID-19 positive cases. Because logistics got backed up or the movement of people visiting their older family members at the villages was restricted due to the pandemic, however, impoverishment of people of all generations was acknowledged as a problem. As the drought added to the problem, issues with food and livestock have become prominent. Masks and vaccination are offered for free in their neighborhoods, but that is not good enough to accelerate people’s behavioral change. Someone also told me that they are not used to wearing masks and so wearing one is so cumbersome that many older people refuse to use them and choose to stay home without going anywhere. Many older people were economically dependent on their sons and daughters in the first place, and the pension system there does not cover all the older people. Because of the pandemic, their children who work far from home lost their jobs or couldn’t get paid, and so are sending less money to their older relatives, with the result that even their daily food was hard to come by. However, they do have some mutual-help programs. Public servants, religious leaders, or others who are financially comfortable enough raise money with which to purchase food and give it to low-income families, older people, and single-person households. Or they provide widows’ households, single mothers, and others who are leading an unstable life with daily necessities such as food and hand soap. Also, people in Kwale once shared their concern with me: women and children get support, but older people seldom get any.

Living Situation and Social Welfare for the Older Persons in Kenya

Ryuji Yoshino (Nagasaki University)

The topic of my presentation is the “Living Situation and Social Welfare for the Older Persons in Kenya.”

In Kenya, the number of daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases averages between 50 and 70, and the positive rate is kept low at 1-2%. They lifted a nightly curfew on October 20 and began extensive vaccination on November 26 with the aim of administering a total of 10 million jabs by the end of December. They have also announced that they will start a COVID-19 vaccination certificate system within the country from December 21. As the number of daily new confirmed cases decreases, so does the number of daily new confirmed deaths, and recently there have been days with no reported deaths. As of November 26, the cumulative number of deaths was 5,333, of which 3,095, or 58%, were aged 60 or over.

If I look at the vaccination rate there, 9.6% of adults aged 18 or over have taken two jabs. For those aged 58 or over, whom the government classifies as “older persons,” only 19.4% have taken two jabs versus their self-set goal, which is still rather low. On the other hand, as high as 80-90% of medical professionals and teaching staff have been fully vaccinated. This slide shows the percentage of persons who have taken two jabs in each county. In Nairobi and other urban neighborhoods, the vaccination rate is high, whereas in counties far from urban centers like the northeastern and northwestern areas, the rate is very low at less than 2%.

Let me move on to talk about the social welfare system for older persons in Kenya. In Kenya, they had a program called the Older Persons Cash Transfer (OPCT) between 2007 and 2017. To be eligible for this system, you had to be an older person aged 65 or over and poor and vulnerable. Also, there is a requirement to be eligible to the OPCT, which a beneficiary is not receiving any pension or enrolled in any other Cash Transfer program. Thus it make them difficult to be eligible. Then in 2018, the Kenya government launched a new regular cash transfer program called Inua Jamii 70+ for every citizen aged 70 or over. As of July 2021, the number of beneficiaries totals 1.1 million. The difference with the OPCT is that it does not have any requirement other than the age of beneficiaries. To increase the number of recipients, the Kenyan government engages beneficiaries of other cash transfer programs and pensioners intto this program. Other than these programs, the Kenyan government also runs social welfare programs for older persons raising orphans and vulnerable children, persons with disabilities, and older persons who have fallen victim to drought and hunger.

Next, I will report on activities by HelpAge International, which is an international NGO dedicated to respecting the human rights of older persons and supporting their active and healthy lives in 86 countries around the world. In cooperation with local NGOs in Kenya, they support social interactions and distribute food to older persons. Furthermore, since 2020 they have conducted a longitudinal survey in Nairobi. Based on a variety of data, such as the rate of older persons receiving regular cash transfers, the percentage of older persons with disabilities, and their living conditions in general, they make policy proposals for the national government to improve the living situation of the older persons.

Let me elaborate on the longitudinal survey of older persons in Nairobi. They surveyed older persons aged 60 or over by collecting data on approximately 4,000 persons and 6,000 persons in areas called Dagoretti and Kibera sub-county, respectively. Though, the survey was affected by the pandemic and a subsequent decision to reduce their budget, the first wave (WAVE1) of this survey was completed in March 2021. To follow up on the quantitative research for the WAVE1 participants, WAVE2 was conducted in October 2021. In addition to the follow-up, they are performing the qualitative research to shed light on the realities of older persons’ lives and the impacts of the cash transfers program, OPCT into the living situation of the older persons. Officiallly speaking, we can not disclose the results of the survey until WAVE3 is over and they published the results; however, with kind permission from a survey staff member, they kindly shared some findings with us and I am at liberty to convey.

First, more than 60% of older persons rarely participated in any social network because of their health issues. Around 20% of older persons had three or more chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes in theif medical history. While about 30% of the participants aged 70 or over are eligible for Inua Jamii 70+, but the results showed that only about 18% of them could receive the benefits. Other findings include that they suffer food insecurity or financial abuse.

I will then talk about the activities of a local NGO called Kibera Day Care Center for Elderly (KDCCE). This NGO covers 21 villages in Kibera sub-county and conducts grassroots activities that cater to specific community needs, such as a soup kitchen and health promotion programs. KDCCE also calls for government agencies to protect older persons’ human rights. This slide shows the highlights of the interviews I did with them in November 2021. The first thing I wish to draw your attention to regarding the impact of the pandemic on the lives of older persons is that few of them die directly from COVID-19. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, this NGO distributes sanitizers, masks, and water tanks for hand-washing to each household to improve the health and hygiene of the residents. In Kibera, most older persons have taken two jabs, which is reassuring, but what is worrying is that, due to the stagnant economic activities resulting from the pandemic, they became more vulnerable to existing issues such as poverty and food shortage. Also, one of the emerging issues is that there have been few new registrations for the Inua Jamii 70+ since 2017, and some of the major challenges for older persons in Kibera include lonliness, being bedridden, and a shortage of caregivers. There, many older persons live alone. They find it hard to invite their children to live with them because that means they have to pay for their education and living costs. On the other hand, some older persons do not have any relatives, restricting their daily lives. Even if they receive the benefits, they still cannot pay their rent and have nowhere to go. It was also reported that more and more older persons are moving out of Kibera. To do something about these issues, in August 2021, KDCCE began collecting 20 Kenyan shillings per week from each resident group member so that they can use the money for emergency support and events designed to revitalize their community. At present, there are more than 30 groups that support older persons’ independence, and each group consists of between 15 and 20 resident members. Those groups serve as places for older persons living alone to gather and provide opportunities for mutual help among the residents, sharing food with other members of the group.

Finally, the survey found that the pandemic has aggravated some of the underlying issues, such as poverty and food shortage. In Kibera, some of the major challenges they face include solitude, bed-ridden older persons, and a lack of caregivers. In conclusion, the government is trying hard to promulgate public social welfare programs such as Inua Jamii 70+, however they have yet to reach many of those who need the support, and improve the quality of life of older persons. Meanwhile, through this interviewed, it realized that the community networks and mutual support within communities by international and local NGOs are being strengthened. And their efforts make the community have advances systems within communities of older persons to help each other through mutual aid. This is the end of my presentation. Thank you for your kind attention.

Comments

Reiko Hayashi (National Institute os Population and Social Security Research)

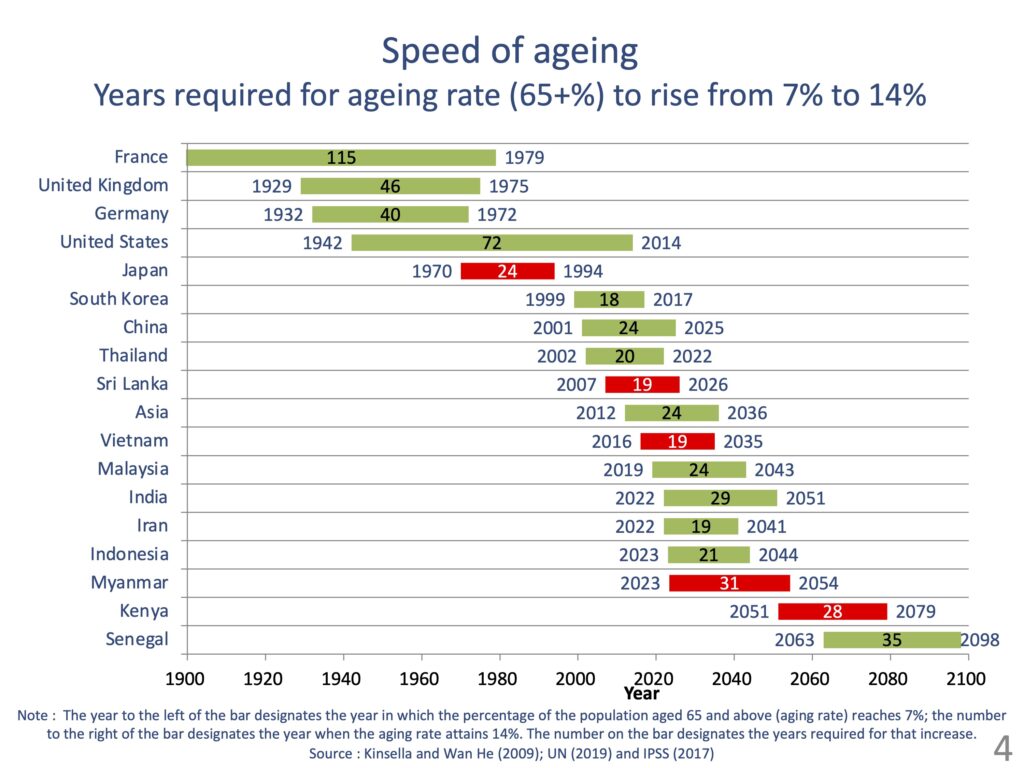

In 2020, amid the pandemic, the Decade of Healthy Ageing was declared, first by the World Health Assembly in August, followed by the U.N. General Assembly in December. The decade of healthy ageing from 2020 to 2030 has begun. I think this means that the world is now in a mood to promote ageing. To check up on where we are in terms of the global ageing, I will discuss the speed of ageing, as you have already shown percentages of older people and population pyramids of specific regions and countries. In Japan, it took 24 years for the percentage of the population aged 65 and above (ageing rate) to increase from 7% to 14%. It is estimated that Sri Lanka should take 19 years, Vietnam 19 years, Myanmar 31 years, which is a bit longer than in other countries, and Kenya 28 years. Because each country reaches 7% at different timings, Kenya still has a long way to go before its ageing rate attains 14%.

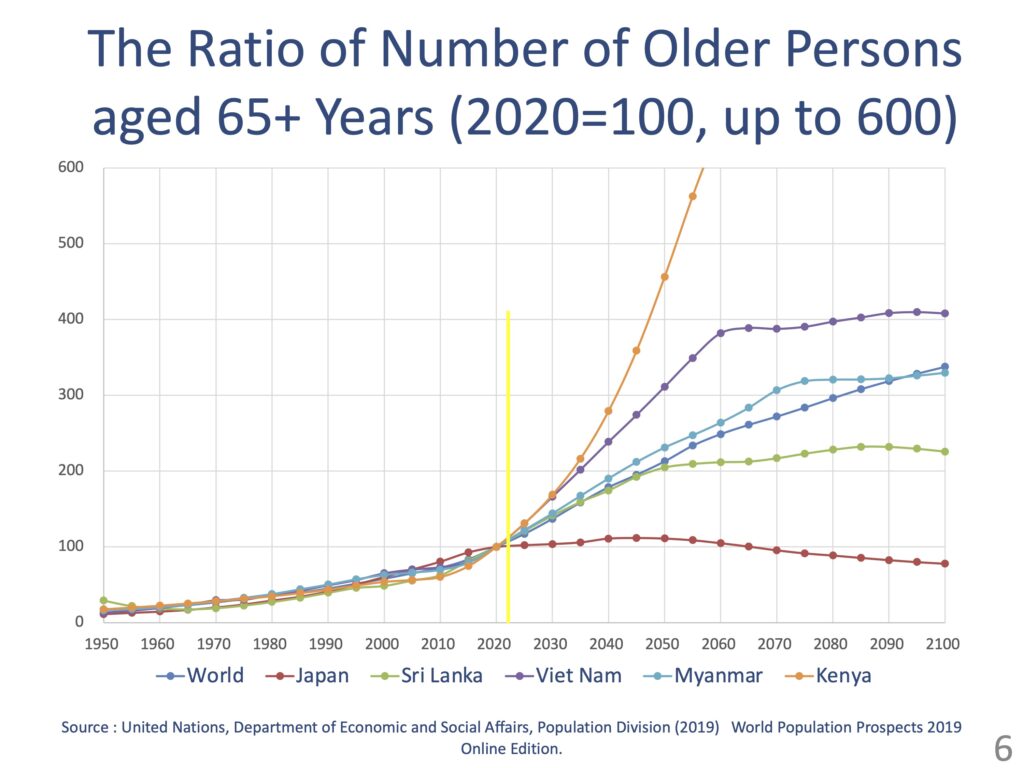

However, if we look at this graph, which shows the anticipated increase in the population aged 65 and above in each country against a 2020 index base of 100, the count in Kenya is expected to grow by far the most. Japan, which currently has the highest percentage of elderly people in the world, will not grow that much in the future. On the other hand, in countries like Sri Lanka and Myanmar, the count should double by 2040. Also, the count in Vietnam and Kenya is expected to skyrocket at an exponential rate. As such, it is not correct to assume African countries still have a long way to go before their populations are aged; as their populations explode at a frightening pace, the number of older people will soar accordingly.

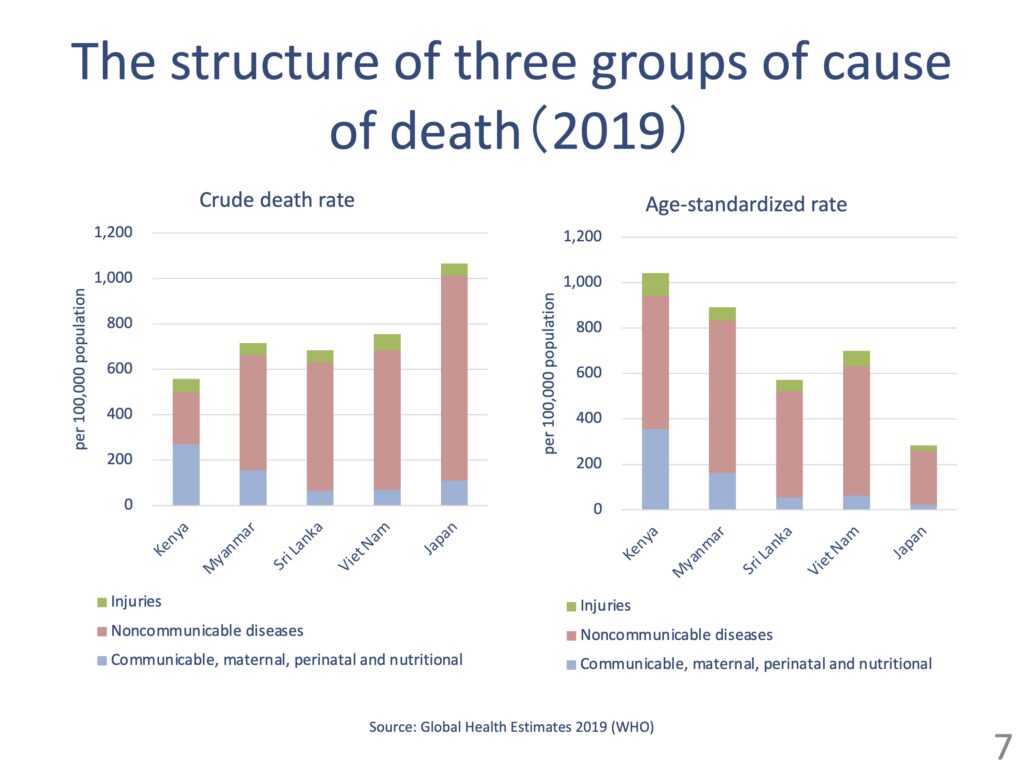

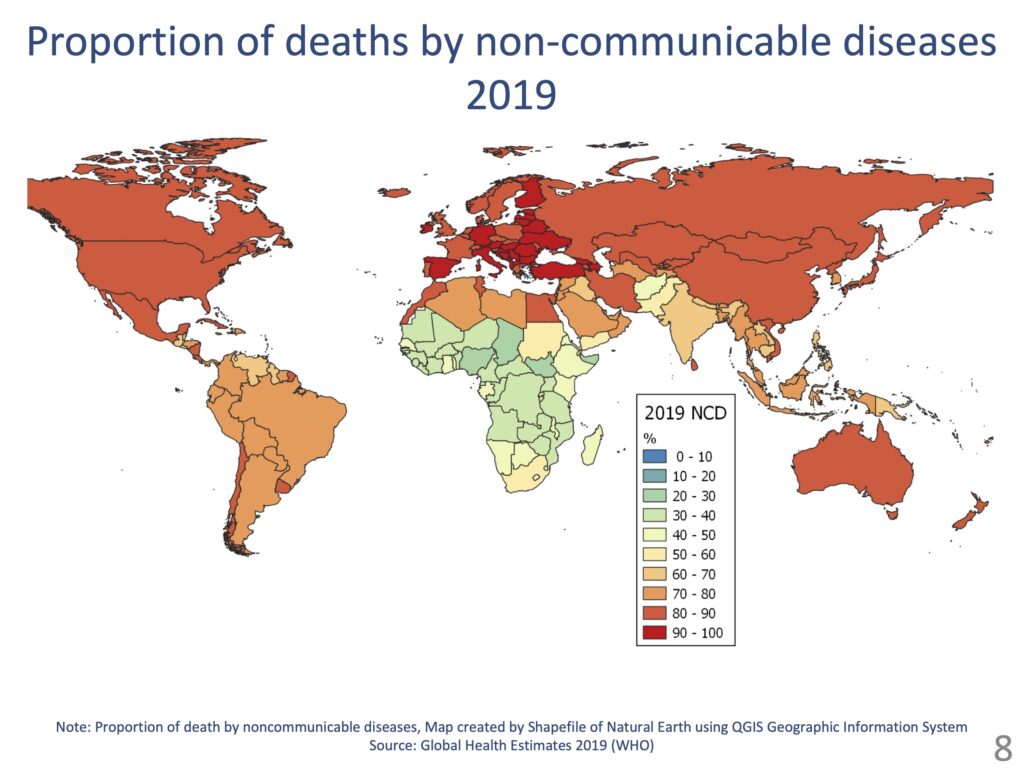

In the past, in the context of international cooperation, it was often said that infectious diseases would shift to chronic diseases as development progressed, as Abdel Omran once put as an “epidemiological transition”. The developing countries were considered to suffer from mainly the infectious diseases. If we group causes of death into the three broad categories of communicable diseases (and maternal, perinatal, nutritional conditions), noncommunicable diseases, and injuries, the top killer in Kenya remains communicable diseases, and the percentage of deaths from noncommunicable diseases is small. This is the case for other countries in Africa as well.

In other regions of the world, however, more than half of deaths are due to noncommunicable diseases. What this means is that an epidemiological transition is over in most countries in the world, including Asian countries; more people die from noncommunicable diseases than from communicable diseases. Back in 2000, when we were talking about the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the number of deaths caused by non-communicable diseases in South and Southeast Asia was still low, but things have changed dramatically over the last 19 years. With this in mind, we need to take new measures to deal with the aging population and chronic diseases.

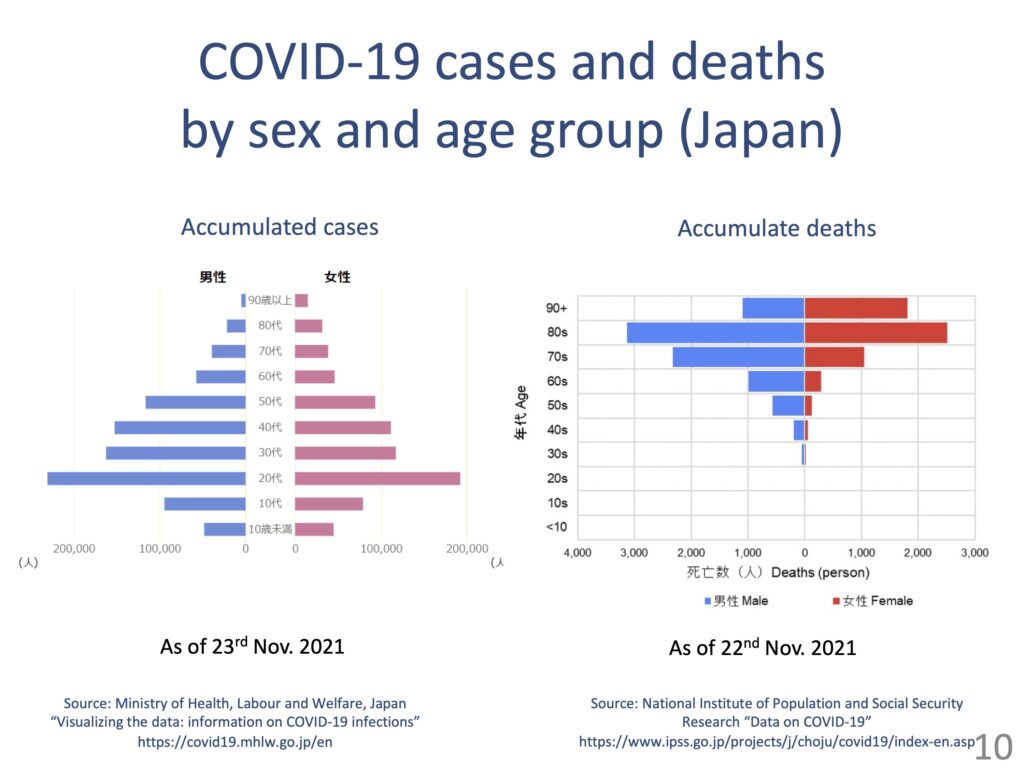

Then, COVID-19 came out of the blue. We have data by age and sex for Japan. As you can see, the cumulative number of positive cases is high for those in their 20s and 30s, but many deaths are reported for older people, especially those in their 80s.

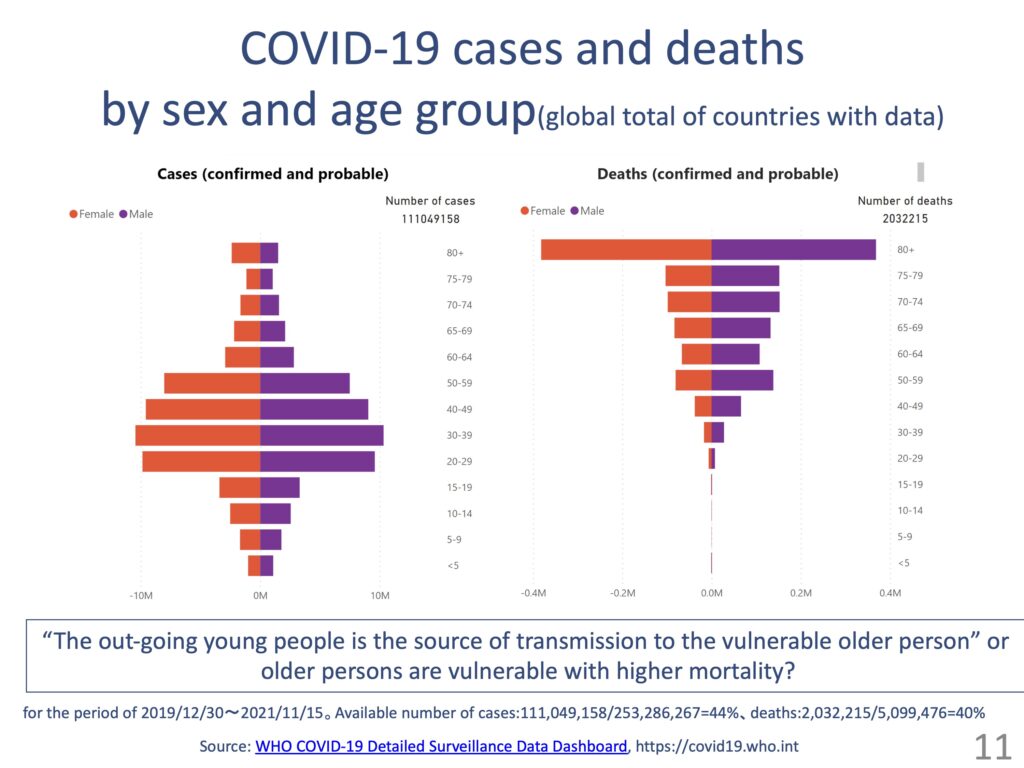

Many countries around the world do not have such data disaggregated by age and sex, and about 40% of such data are reported to the World Health Organization (WHO). If we look at the data, many new positive cases are reported for younger people, but the number of deaths is disproportionately high for those in their 80s or above.

You could interpret this in two ways: infected younger people go out and spread the virus to vulnerable older people, or it just happens that way as the mortality of older people is higher than that of younger people in the first place. Perhaps it is a matter of degree, but I presume the latter is truer in Japan. The other day, it was reported that an infant died from COVID-19 in Indonesia, and I guess the truth is that it is the most vulnerable that fall victim to COVID-19.

This symposium has yielded a variety of points in question. Dr. Shobugawa reported that the mortality rate is higher for people who have lost communication with others. On the other hand, it seems that access to healthcare services is not a significant factor. The social relationships are often more important than access to healthcare services, as Dr. Yoshino reported also at the end.

Speaking of Dr. Horii’s report, I would like to ask about the education of care givers according to the needs of the population. In other words, since Japan has accepted Vietnamese people, the education of care givers, including Japanese language education, has become popular in Vietnam, but are middle-income countries like Vietnam developing human resources who can cope with the increasing number of chronic diseases in their own countries? Japan, too, went through many events during the 70s but managed to get by. I believe that many countries share questions of where we should draw the line between nurses and caregivers on the one hand and nursing and long-term care on the other and how we should develop relationships between the two.

On the topic of “a trade-off between community support and restriction,” Dr. Nomura surprised us the story of Sri Lanka where they put up a poster saying “Infected with COVID-19” on the wall of the patient’s house. Although the community is important, we must never forget that too much emphasis on the community can make one restricted by its bonds. Also, the spread of mobile phones may not be due to COVID-19, but it is safe to say that the devices have significantly impacted older people.

From the reports by Dr. Miyachi and Dr. Yoshino, we learned that many older people live alone in Africa, too. We may get a different perspective if compared to South Asia. Mobility of older people is another point in question. In some cases, the elderly are unable to move and in other cases, they go back and forth to their relatives. In what living arrangement older people are in is also an important issue.

Lastly, there is the question of what impact COVID-19 has had on older people overall. The answer differs so much among countries. For example, as some presenters mentioned, the number of deaths from COVID-19 in Africa is relatively small, and they are more vulnerable to drought, restrictions of activities and a stagnant economy than to COVID-19. I think that we need to take countermeasures while making calm judgments based on the circumstances of each country. I look forward to the further discussions on this issue.